New Year, Same Great Films

4 January 2018

New Releases A Happy New Year from everyone at Filmhouse! We're looking forward to...

Almost sixty years since it was first presented in cinemas Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho still exerts a considerable influence over representations of screen violence. This is the central thesis of an exhaustive new documentary by Swiss-American filmmaker Alexandre O. Philippe called 78/52, which is screening in tandem with Hitchcock’s macabre masterpiece at the Filmhouse this month.

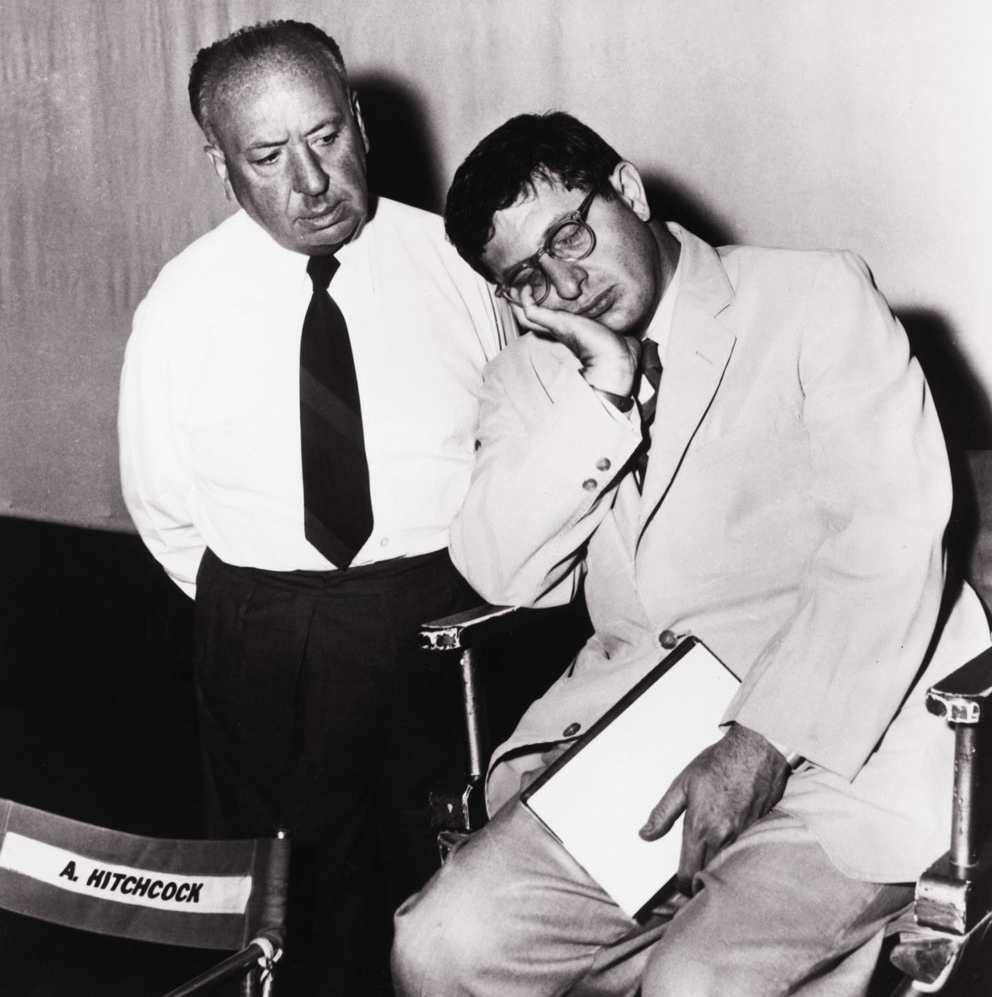

Philippe is a genre cinema enthusiast who has previously directed feature-length documentaries examining the rise of the zombie movie - Doc of the Dead (2014) - and the problematic fandom surrounding the Star Wars franchise - The People vs. George Lucas (2010). Mixing fanboyish factoids with genuinely informative industry insight is very much Philippe’s MO as a documentarian, and with 78/52 he has gathered together a diverse, multi-generation straddling cast of commentators to reflect, in detail, on what amounts to around three minutes of screen time. After all this isn’t an analysis of Psycho as a film phenomenon, but rather a dissection of one of the most infamous scenes in film history, and one which Philippe clearly believes changed everything in cinema. Alfred Hitchcock and Janet Leigh on the set of Psycho

Alfred Hitchcock and Janet Leigh on the set of Psycho

Taking a look at the 78 cuts and 52 shots that comprise the shower sequence in which Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane meets a grisly end, what Philippe’s film does, more than anything else, is shine a light on the collaborative process between Hitchcock, his composer Bernard Herrmann and the expert work of unheralded editor George Tomasini. It is Tomasini whose work is really brought to the fore in the documentary, particularly through the musings of fellow editors Walter Murch and Amy E. Duddleston. By focusing upon the editor’s role in crafting such a visually complex piece of Hollywood cinema, the film drives against the auteurist impulse in a lot of cinephilia, and partly explodes the myth of Hitchcock as a director entirely in control of his material through meticulous pre-planning and an unswerving commitment to the storyboard. Alfred Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann

Alfred Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann

Tomasini’s considerable input into this key scene in Hitchcock’s filmography, also raises a question about just how vital collaboration was for the director, particularly when you consider that this working relationship begins on Rear Window (1954), and carries on through every film of Hitch’s white-hot streak that ends with Marnie (1964) a decade later. The fact that Amy E. Duddleston, who was Gus Van Sant’s editor on the 1998 remake of Psycho, talks so candidly to Philippe about that film’s inability to harness new film technology to improve upon Tomasini’s edit, speaks volumes for how an intensely fertile collaborative relationship can dynamically transform the execution of a scene. Anne Heche in Gus Van Sant's 1998 Psycho remake

Anne Heche in Gus Van Sant's 1998 Psycho remake

78/52, by falling somewhere between the cinephilic sinecure of Kent Jones’ Hitchcock/Truffaut (2015) and the rambling myth-making of Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 (2012), manages to be both entertaining and erudite, accessible and immersive. Although I do not agree with some of the grand claims that Philippe cannot resist making for Psycho – such as, it being the origin point of the slasher sub-genre, especially bearing in mind that Michael Powell’s similarly themed and far more disturbing Peeping Tom (1960) makes it to cinema screens a full month ahead of Hitchcock’s film – it is these regular provocations that make 78/52 so engaging. For every commentator that offers up a succinct critical insight – Karyn Kusama’s assertion that Psycho represents ‘the first modern expression of the female body under assault’, for example – there is another who will take the viewer down an infuriating blind alley of pop cultural name-dropping (how else to explain the Game of Thrones comparison crowbarred in). The limitations and the merits of film analysis can be found in every cut and slash of Philippe’s editorial eye.

Have a look at what's on to book a screening or event.

Still adding?

If you don’t want to view your Watch list right now, you can access your list anytime from your profile.